“Through the image is sustained an awareness of the infinite: the eternal within the finite, the spiritual within the matter, the limitless given form.”

– Andrei Tarkovsky

I. Introduction

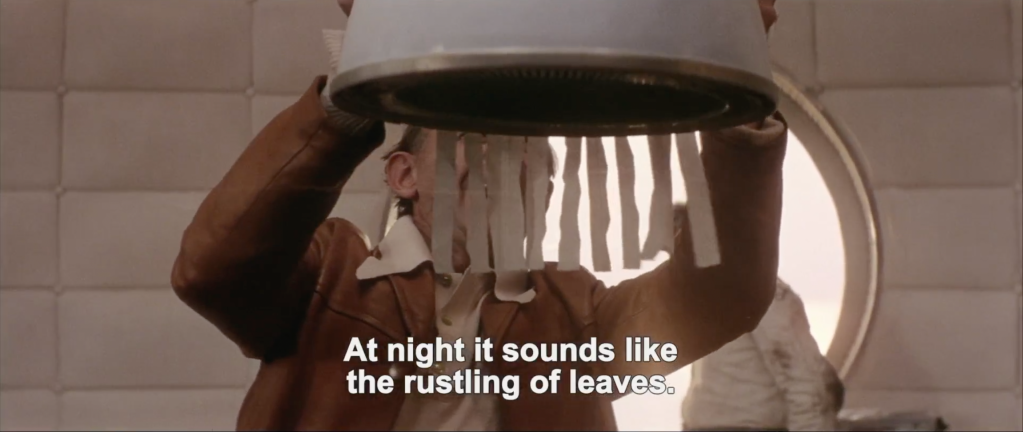

Solaris, 1972: Snaut stands, his back toward the camera. Kris is beside him, framed by a circular window that looks out into the Ocean. It is morning; the Ocean is the color of lilac. Kris turns away from Snaut, leaning against the window in side profile. He rubs his eyes, the bridge of his nose. Night is the best time here. It somehow reminds me of Earth. Snaut turns around, revealing a piece of paper cut into strips. Snaut approaches the camera and pulls a vent down from the ceiling. Attach strips of paper to the air vents. At night it sounds like the rustling of leaves.

I remember watching Solaris for the first time and being struck by this moment. I remember the feeling of revelation; Andrei Tarkovsky was saying something declarative about the nature of his cinema. In the practice of filmmaking, the artist is constantly striving, through artifice, to arrive at an image that produces the experience of something real. On the Solaris space station, Kris Kelvin is longing for the earthly in a place where that is impossible. Snaut offers an alternative: what if the feeling of the real, the sound of rustling leaves, could be produced artificially? As a spectator, a mirrored thought arises: can the experience of something real—a true emotion, a moving moment, a mystical experience—be provoked by the artificial construction of a cinematic image? Just after this scene, Tarkovsky cuts to a shot of Kris sleeping. Hanging from the vent in his room are those same strips of paper. It sounds like the rustling of leaves.

A year before his death, Tarkovsky published a book about art and filmmaking titled Sculpting in Time. He wrote extensively about the image (obraz) imbued with such a transcendent capacity: “I can only say that the image stretches out into infinity, and leads to the absolute.”1 Within his definition of the image, Tarkovsky holds something material, the physical existence of the filmic image, and something metaphysical, the unique capacity of an image to reveal something truthful beyond itself. He writes,

The image is an impression of the truth, a glimpse of the truth permitted to us in our blindness. The incarnate image will be faithful when its articulations are palpably the expression of truth, when they make it unique, singular—as life itself is, even in its simplest manifestations.2

These images are of supreme importance. They are the radical moments in which the real reaches out, grabs us, and produces an experience beyond what we expect. Put simply, they are moving. Put poetically, in Tarkovsky’s words, “the image is not a certain meaning, expressed by the director, but an entire world reflected as in a drop of water.”3 If a filmmaker achieves even one such image, the moment produced is a feeling, described by Christian Keathley in Cinephilia and History, as “nothing less than an epiphany.”4

In this moment from Solaris, Tarkovsky speaks directly to the spectator and deconstructs his filmmaking practice. He lifts the hood and reveals the mechanics: strive to reveal something authentic, some inner truth of things, through the construction of the moment. The ultimate goal is to arrive at the real through means of representation, through filmmaking itself. He writes, “Can these impressions of life be conveyed through film? They undoubtedly can; indeed it is the special virtue of cinema, as the most realistic of the arts, to be the means of such communication.”5 Once taught to watch this way, to look for the transcendent impressions of life and truth, the spectator begins to relate to cinema with radical sensitivity to the power of the image. Tarkovsky taught me how to watch.

II. Learning to Look

How is the spectator to identify moments that produce these experiences of the real, the moments where, fleetingly, strips of paper become rustling leaves? What separates these kinds of moments from those which lack the capacity to move us, the moments where the paper is just the filmic representation of paper and nothing more? I turn to Keathley’s writing on the cinephiliac moment. Citing Paul Willimen, Keathley writes that cinephiliac moments are,

“fleeting evanescent moments” in the film experience. Whether it is the gesture of a hand, the odd rhythm of a horse’s gait, or the sudden change in expression on a face, these moments are experienced by the cinephile who beholds them as nothing less than an epiphany, a revelation.6

To simplify Keathley’s project in Cinephilia and History, cinephiliac moments are those moments which are not designed to provoke epiphany, yet nevertheless, do. They are not the climaxes or set pieces, but marginalia. Keathley turns to a brief essay in Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida to elucidate his argument.

In Camera Lucida, Barthes describes two qualities of the image: the studium and the punctum. Although Barthes was writing about still photography, Keathley extrapolates his argument to the film image. We can think of the first part of the image, the studium, as that which is designed. Barthes suggests that when we recognize the studium we “inevitably encounter the photographer’s intentions.”7 The studium is the deliberate aestheticization of the image, those components where we can feel the hand of the director. In cinema, this could include camera movements, editing choices, or mise-en-scène.

The punctum, on the other hand, is to Barthes “this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me.”8 The punctum possesses “potentiality, a power of expansion. This power is often metonymic.”9 Barthes’ philosophy of the punctum is strikingly similar to a famously elusive concept in film studies: photogénie. Keathley writes, “As with the cinephiliac moment, photogénie results not from what has been aestheticized, but from the real shining through deliberate aestheticization.”10 The punctum shining through the studium could be conflated with photogénie and the eruption of the real. No matter what it is called, the experience is the same—an undeniably mystical response to art. Simply put, this response is the momentary blurring of boundaries between the self and something larger. However, an encounter with a work of art, with cinema, is not guaranteed to produce mystical experience. But, to transform a moment into a cinephiliac moment, within the image there must exist a punctum.

Barthes notes, “whether or not it is triggered, it is an addition: it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there.”11 In this statement, Barthes acknowledges the necessity of the spectator’s response in producing the punctum. The potential for a punctum exists within every photo, yet it depends on the participation of the spectator to become active. The punctum is subjective, individual. This cannot be overstated: what I am interested in is affect. The film produces the moment, but without the spectator, there is no punctum. While discussing the difference between the pornographic and the erotic in the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe, Barthes writes, “The punctum, then, is a kind of subtle beyond—as if the image launched desire beyond what it permits us to see: not only toward ‘the rest’ of the nakedness, not only toward the fantasy of a praxis, but toward the absolute excellence of a being, body and soul together.”12 Barthes’ writing on the punctum draws on similar ideas as Tarkovsky’s writing on the image; both are concerned with the transcendent capacity of the visual world.

There is a word in the study of comparative religion, hierophany, which means the appearance of the sacred or holy.13 In his writing on hierophanies in Patterns of Comparative Religion, Mircea Eliade writes that a hierophany is “a manifestation of the sacred in the mental world of those who believed in it.”14 To Eliade, “A thing becomes sacred in so far as it embodies (that is, reveals) something other than itself.”15 For Barthes, finding the punctum in a photograph is a hierophany. For Keathley, the cinephiliac moment functions much the same. What is clear to Eliade is something radical:

We must get used to the idea of recognizing hierophanies absolutely everywhere, in every area of psychological, economic, spiritual and social life. Indeed, we cannot be sure that there is anything—object, movement, psychological function being or even game—that has not at some time in human history been transformed into a hierophany.16

Eliade argues that “anything man has ever handled, felt, come in contact with or loved can become a hierophany.”17 Perhaps, even the cinema.

A question that brings me back to the moment from Solaris is whether these moments, these hierophanies, can be designed. Can a director—sensitive to the power of the cinephiliac moment, the punctum, hierophanies—create the conditions necessary to elicit this kind of response from the spectator? If so, how? Within his filmography, Tarkovsky seems to pose this very question. Can the rustling of air conditioning through strips of paper sufficiently transcend its materiality and produce the experience of something real, the wind rustling through leaves?18 Can cinema transcend its materiality and produce the experience of something real? The measure of success is affect. On the Solaris space station, is the real made accessible to Kris? The earthly in this impossible unearthly place? Despite the successful mimesis of the sound of the wind rustling through leaves, Solaris seems to suggest this is not the case; in the end, Hari is not Hari and she knows it. Yet, when I consider this moment as containing Tarkovsky’s entire cinematic project, his “entire world reflected as in a drop of water,” I understand that despite the near inevitability of failure, and the impossibility of achieving complete success—the real in the artistic image in its complete, undegraded form—the artist continues anyway.19

Tarkovsky was equal parts artist and aesthetician. At times, he succeeded in producing art that embodied his lofty aesthetics. At times, he failed. In Keathley’s examination of the cinephiliac moment, he begins with the assumption that these moments cannot be designed. Their power is inextricably linked to the punctum, which is beyond the hands of the filmmaker. But perhaps the sensitive filmmaker can produce optimal conditions to elicit this kind of response. I am entertaining the idea that if a filmmaker internalizes the mystical, perhaps as Paul Schrader argues through the stylistic practice of a transcendental cinema, or in the case of Tarkovsky through the perfection of slow cinema, then the cinematic project becomes designing these sites for epiphany.20 The relative success of these designed moments implicates the viewer. Our affect, whether we are moved, whether the meditative quality of the long take is a sufficient avenue for transcendence, is the only metric of success. In this project, I explore one moment from each of Tarkovsky’s seven feature-length films to better understand these experiences and what they reveal about Tarkovsky’s filmography, my practice of spectatorship, and the act of writing from these experiences.

III. Cinema and the Mystical Experience

What is the affect we experience, this feeling of being moved? What feelings mark these experiences as identifiably mystical and separate them from other cinematic experiences? Although Barthes and Keathley do not evoke the mystical, I have found it productive to look to William James, who famously compiled his lectures on mystical experience in 1902 as The Varieties of Religious Experience. In one lecture he offers four qualities which, when experienced, may justify the designation of an experience as mystical. The framework he outlines for classifying these experiences proves invaluable when considering the revelatory experience of the moment as it steps into our lives and changes us.

The first mark of mystical experience is ineffability. James writes that subject of the experience—for our purposes, the spectator—immediately reports that the experience

defies expression, that no adequate report of its contents can be given in words. It follows from this that its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others. In this peculiarity mystical states are more like states of feeling than states of intellect. No one can make clear to another who has never had a certain feeling, in what the quality or worth of it consists.21

Tarkovsky offers a similar sentiment regarding the image’s capacity to reveal infinity, taking the experience of ineffability a step further by suggesting its capacity to be communicated through art. Tarkovsky writes, “The idea of infinity cannot be expressed in words or even described, but it can be apprehended through art, which makes infinity tangible. The absolute is only attainable through faith and in the creative act.”22 In writing about ineffability, James also notes something that comes up time again when considering the moment: the idea that it is not universally accessible. James suggests that “One must have musical ears to know the value of a symphony; one must have been in love to one’s self to understand a lover’s state of mind. Lacking heart or ear, we cannot interpret the musician or the lover justly, and are even likely to consider him weak-minded or absurd.”23 Perhaps the same is to be said of the cinephiliac moment—only those with the eyes to see, those sensitive and open to the experience—can experience them in fullness. As a caveat to James’ argument, I might suggest that this type of spectatorship can be learned, but only once the spectator is made aware of the moment’s mystical capacity and is taught how to watch.

The second mark of mystical experience is its noetic quality. James writes,

Although so similar to states of feeling, mystical states seem to those who experience them to be also states of knowledge. They are states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect. They are illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance, all inarticulate though they remain: and as a rule they carry with them a curious sense of authority for after-time.24

The first part of James’ description is clear enough. The noetic quality of mystical experience is felt rather than understood. Tarkovsky articulated a similar sentiment, differentiating between two types of understanding. He writes, “Understanding in a scientific sense means agreement on a cerebral, logical level; it is an intellectual act akin to the process of solving a theorem. Understanding an artistic image means an aesthetic acceptance of the beautiful, on an emotional level or even supra-emotional level.”25 He described this second type of understanding as “the idea of knowing, where the effect is expressed as shock, as catharsis.”26 Such experiences reveal truth yet retain mystery when brought to the level of reason. Put poetically, Tarkovsky writes, “It’s a question of sudden flashes of illumination—like scales falling from eyes; not in relation to the parts, however, but to the whole, to the infinite, to what does not fit in to conscious thought.”27 In these moments, it is as if the trite exterior of a cliché is scraped away and all of a sudden the core of its truth is blindingly revealed. Tarkovsky suggests, “And what are moments of illumination if not momentarily felt truth?”28 The last bit of James’ description of noetic quality, the “curious authority for after-time,” is of particular interest, especially as we consider these qualities as a framework for understanding the moment. After-time is the experience’s capacity to change us, the lingering quality. It is also the ability to recognize these experiences when they recur. After-time raises the question of authority. As put by Keathley, there are moments in cinema which “displace themselves out of their original contexts and step into our lives.”29

The mystical experience’s capacity to change us leads us to the third mark of mystical experience: transiency. James notices,

Mystical states cannot be sustained for long. […] Often, when faded, their quality can but imperfectly be reproduced in memory; but when they recur, it is recognized: and from one recurrence to another it is susceptible of continuous development in what is felt as inner richness and importance.30

Since these experiences cannot be sustained, they must have a lasting capacity to grant them authority. Transiency is especially relevant given the temporal nature of cinema. Tarkovsky describes the essence of the director’s work as “sculpting in time.”31 The director, from a “lump of time,” shaves off the excess to reveal what will prove to be the true expression of the cinematic image.32 The moments I work with rarely last more than a few minutes, and the punctums held within them no longer than a few seconds. The fleeting quality of these moments is complicated only by our ability to repeatedly return to them.

The final quality of mystical experience is passivity. The mystic may facilitate the oncoming of such an experience. In a religious context, this could include any number of practices across faiths, such as beginning a meditative or contemplative practice. This setting of the stage is within the control of the mystic. The same can be said of the spectator. The spectator may choose a film and a setting, thereby providing the conditions which are necessary for a moment to arise. The spectator may also prime themselves to be moved, opening their heart and practicing a form of looking known as the panoramic gaze.33 Yet, James says, “when the characteristic sort of consciousness once has set in, the mystic feels as if his own will were in abeyance, and indeed sometimes as if he were grasped and held by a superior power.”34 This too is true of the spectator’s experience of the moment. The cinephiliac moment balances the active spectator-centric punctum with the feeling of passivity that is inherent even to the most active forms of watching. Once the film and context are selected, the spectator is left with no choice as to what happens next within the diegetic world of the film. Simply put, the spectator is held by the superior power of the author. James clarifies the authority derived from these moments of mystical consciousness, writing, “They modify the inner life of the subject between the times of their recurrence.”35

In his lectures on mysticism, James was primarily concerned with religious experience. However, he also makes note of art’s capacity to elicit similar experiences of mystical consciousness. James writes,

Single words, and the conjunction of words, effects of light on land and sea, odors and musical sounds, all bring it when the mind is turned aright. Most of us can remember the strangely moving power of passages in certain poems read when we were young, irrational doorways as they were through which the mystery of fact, the wildness and the pang of life, stole into our hearts and thrilled them. The words have now perhaps become mere polished surfaces for us; but lyric poetry and music are alive and significant only in proportion as they fetch these strange vistas of a life continuous with our own, beckoning and inviting, yet ever eluding our pursuit. We are alive or dead to the eternal inner message of the arts according as we have kept or lost this mystical susceptibility.36

I might add the cinephiliac moment to James’ list of art with the capacity to move us toward the mystical.

IV. Writing from Ineffability

The subjective experience of spectatorship lies at the very heart of this project. Keathley quotes Paul Willemen, “There are moments which, when encountered in a film, spark something which then produces the energy and the desire to write, to find formulations to convey something about the intensity of that spark.”37 In this project, I have compiled one moment from each of Tarkovsky’s seven feature films that sparked something in me and produced the desire to convey something essential and true about the intensity of that spark. Each of the moments I selected produced the feeling of epiphany and could be described as cinephiliac moments, perhaps even hierophanies. I recognized these experiences in line with James’ four pillars of mystical experience. Some are marginalia, like the smile of a little girl in Andrei Rublev. Others are primary but mysterious details, such as the dog in Nostalghia. In my writing on Mirror and The Sacrifice, I reckon with the realism and the repetition of an image. In my writing on Ivan’s Childhood I take a page from Keathley’s playbook on writing the cinephiliac anecdote and practice writing metonymically, asking “What can follow what I say? What can be engendered by the episode I am telling?”38 I use the collective mythology of Biblical stories to unravel a moment from Stalker. In all of these pieces, I am negotiating how to write from the ineffable. When pierced by an image and moved by a cinematic epiphany, how can I communicate a feeling whose purity of essence depends on defying language? I offer five distinct experiments in writing from ineffability.

In the closing paragraphs of Mythologies, Barthes describes two “equally extreme” critical methods, ideologizing and poeticizing,

we constantly drift between the object and its demystification, powerless to render its wholeness. For if we penetrate the object, we liberate it but we destroy it; and if we acknowledge its full weight, we respect it, but we restore it to a state which is still mystified. It would seem that we are condemned for some time yet always to speak excessively about reality. This is probably because ideologism and its opposite are types of behavior which are still magical, terrorized, blinded and fascinated by the split in the social world. And yet, this is what we must seek: a reconciliation between reality and men, between description and explanation, between object and knowledge.39

Writing from each of these seven moments, I attempt to strike a balance between ideologizing and poeticizing, leaning at times closer to one of these critical methods than the other, but always conscious that the opposite tendency is revelatory. Regardless of the method, through writing out of these moments I seek to illuminate something true, as Keathley puts it, “the ways in which movies—especially moments from movies—displace themselves out of their original contexts and step into our lives.”40

Tracing back the origins of this project, it is clear to me now that the moment from Solaris holds the seed of my critical argument. The image of the strips of paper taped to the air vent holds the entirety of my project, the “entire world reflected as in a drop of water.”41 Watching Solaris for the first time, I had the uncanny feeling that Tarkovsky was speaking directly to me, understanding exactly what I was trying to say about the nature of his cinema. The first hierophany was hearing the rustling of wind through the leaves.

- Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, trans. Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1987), 104. ↩︎

- Ibid, 106. ↩︎

- Ibid, 108. ↩︎

- Christian Keathley, Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in the Trees (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 6. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 23. ↩︎

- Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 6. ↩︎

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981), 28. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 45. ↩︎

- Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 100. ↩︎

- Barthes, Camera Lucida, 55. ↩︎

- Ibid, 59. ↩︎

- “Hierophany, n. Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary,” in Oxford English Dictionary, accessed January 18, 2024, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/hierophany_n?tab=etymology#1223473880. ↩︎

- Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion, trans. Rosemary Sheed (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1958), 10. ↩︎

- Ibid, 13. ↩︎

- Ibid, 11. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- A beautiful synchronicity: one of Keathley’s epigraphs in Cinephilia and History is a quote from D.W. Griffith from 1944, “What’s missing from movies nowadays is the beauty of the moving wind in the trees.” Keathley later cites another usage of the phrase where Kracauer quotes Griffith, “films conform to the cinematic approach only if they acknowledge the realistic tendency by concentrating on actual physical existence— ‘the beauty of moving wind in the trees.’” Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 115. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 108. ↩︎

- Paul Schrader, “Rethinking Transcendental Style,” University of California Press, n.d., 9. ↩︎

- William James, “Lectures XVI and XVII: Mysticism,” in The Varieties of Religious Experience, ed. LeRoy Miller (Denver, Colorado: Brooks Divinity School, 1999), 252. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 39. ↩︎

- James, “Lectures XVI and XVII: Mysticism,” 252-255. ↩︎

- Ibid, 253. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 40. ↩︎

- Ibid, 36. ↩︎

- Ibid, 41. ↩︎

- Ibid, 43. ↩︎

- Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 152. ↩︎

- James, “Lectures XVI and XVII: Mysticism,” 253. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 64. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “‘Panoramic perception’: this is the tendency to sweep the screen visually in order to register the image in its totality, especially the marginal details and contingencies that are most common sources of cinephiliac moments. Indeed, this spectatorial tendency increases the possibility of encounters with cinephiliac moments.” Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 8. ↩︎

- James, “Lectures XVI and XVII: Mysticism,” 253. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- James, “Lectures XVI and XVII: Mysticism,” 255. ↩︎

- Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 140. ↩︎

- Ibid, 142. ↩︎

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (Canada: HarperCollins, 1972), 158. ↩︎

- Keathley, Cinephilia and History, 152. ↩︎

- Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 108. ↩︎